Literature’s Nobel Prize Winner and Us

I think all who champion the cause of women’s leadership and ordination within an oppressive and suppressive institution like the Catholic Church could relate to the body of works of the Nobel Prize for Literature honoree, Abdulrazak Gurnah. Furthermore, and more significantly, I think all those who perpetuate this oppression and suppression could learn, grow, and benefit immensely by closely reading the stories he tells.

Credit: Getty Images

Abdulrazak Gurnah writes of life in colonial and post-colonial Africa with poignancy, insight, sometimes humor, always wisdom. His is a voice we all need to hear and try to understand because we have not heard nor, even more importantly, understood perspectives and experiences like his nearly enough.

When voices have been silenced, or relegated to prescribed parochial settings only, or ignored or dismissed, we not only lose the ideas and expressions and insight and wisdom they would have brought us, we also lose what we read in Gurnah’s work, their influences, that great body of memory, custom, and experience, of struggles and suffering, of sources of resilience and revelation, of tales of triumph despite all. In essence, we lose the magnificent prose and poetry of lives we never knew before.

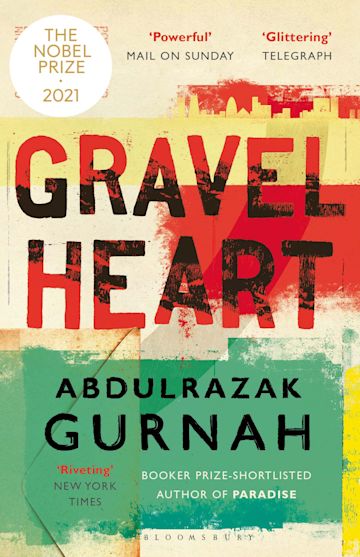

Gurnah writes of mainly of colonialism’s impact, and we can both relate and understand because we already know the effect spiritual colonialism has had on our own lives. In an October 10, 2021 New Yorker article “The Impact of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Nobel Prize” author Kristen Roupenian describes passages from his book, Gravel Heart and then adds:

In Gurnah’s characteristic style, the narrative is woven through with what can feel like digressions: meditations on photographs, letters, and other artifacts; sensory flashbacks, anecdotes, hypotheticals—all the scattered aide-mémoire that are relied on by those who are displaced. Salim’s father’s story, meanwhile, is told in a compelling, propulsive rush. It’s the kind of clean, plot-driven tale created by people who have spent their whole lives polishing an answer to a fundamentally unanswerable question: Why did this happen to me?“

We can find our own encouragement in finally having the resources of those displaced described. We can thrill in seeing them woven into narratives that add context to the displacement. With each reading, we can better understand the losses our Western colonialism has engendered throughout the world and even, hopefully, gain some perspective on how to redress them. And then, particularly as women and other-gendered having lived under a religious colonial power, we can explore further our own losses and gains and bring them forth for all to see. For, like Gurnah, we do want to know, this time from the male hierarchy: Why did this happen to us?

Kristen Roupenian highlighted another passage in Gravel Heart that I think illuminates our situation as well. The main character, Salim, asks his father, “Did you ever read ‘Measure for Measure’?” His father replies he has never completely understood Shakespeare. Salim then gives him a lengthy plot summary and points out how their own family’s tragedy is reflected in “Measure for Measure”. However, Salim adds, his father’s role in their own story is so negligible that “he has no equivalent counterpart in Shakespeare’s play.” The father replies, “I will not bother to read it then,” he says, “if there is no part for me.”

When we have only a minor part of an imposed tradition, we turn – or walk – away.

Abdulrazak Gurnah grew up in Zanzibar. He read some literature in his own language, Kiswahili; he attended British colonial schools where lessons were in English, and he studied the Quran at the local mosque. Rouperenian saw this multi-faceted background as critical: “To appreciate the work of Abdulrazak Gurnah, or any writer, we have to have some knowledge of the tradition to which the writer belongs—to have read some of the books that gave rise to his or her register. Otherwise, how can we understand what the writer is trying to accomplish, the voices she is speaking back to, her allusions and intertextualities? Because of the extraordinary cultural dominance of English, “this makes it easier to forget all the other streams of influence: the Kiswahili poetry, the Islamic tales, even the fusty British-colonial schoolbooks that shaped generations of writers all across the globe.”

In the end, it comes down to: How do those we have marginalized or dominated understand their world? Rouperenian has a suggestion:

We can use that opportunity to grab another book or two that might deepen our appreciation of Gurnah’s register—perhaps a collection of Kiswahili poetry or travel narratives, or “The Thousand and One Nights,” or a novel by another great East African writer, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o . . . or even Shakespeare’s ‘Measure for Measure’.”

But there is another question particularly relevant for us: How do we who have experienced our own marginalization and domination help others understand our world?

My own and others’ suggestions: Bring our unique influences to the forefront. Claim a major role in the narrative of our spiritual and religious life. Write, speak, zoom, gather, witness, make noise, make peace, pray, show up for each other, proclaim, celebrate…and whatever else we can think of. We do not know why this happened to us, but we will not let it continue. We are all in communion and we will not be denied.

With that last sentence in mind, I end with a practical suggestion. I urge all who can to show up for “Bread Not Stones,” a peaceful witness at the Baltimore U.S. bishops meeting who are voting on whether to deny Communion to President Joseph Biden and other prominent Catholics. Through this witness we will state it is wrong to weaponize sacraments, and we will affirm the freedom of conscience of all people.

November 15, 2021 at 1 pm

At the Courtyard by Marriott

Downtown/Inner Harbor

1000 Aliceanna Street, Baltimore, MD

RSVP at the Catholic Organizations for Renewal website.